Author: admin

Mapping Haggadah printed editions (and being careful about it)

The bibliography of the Hebrew Book (BHB) database is an essential reference tool for Jewish studies, made available by the National Library of Israel. Yet, similar to many other library resources, it functions mainly within the limited search paradigm, in which the user is always conceived as looking to find a specific book, or several books, and the user interface is there to help in the retrieval. But the valuable data collected, years of expert work that were put into this knowledge base can also be used differently when liberated from the search interface and made available for enrichment, analysis and visualization.

In the framework of the project DiJeSt, with Dr. Yael Netzer and Dr. Kepa J. Rodriguez, we prepared the Bibliography of the Hebrew Book database for “Distant reading” by processing date and place of publication, and modelling the data according to standard ontologies. For now, I am sharing a part of it as a passover treat, along with some notes on the promises and perils of distant reading datasets.

In the following map you can see all the places documented in the BHB where Haggadah editions were printed, with their languages of translation. By pressing the side button, a legend will open that will help you explore. Clicking a pin will also open the details of an edition published in that place.

When data is available for distant reading, we can often see historical, geographic and other patterns that are more difficult to perceive when looking at records more closely. Interesting outliers are also more visible this way: why were English translations printed in Hannover, or Fuerth? or a Judeo-Arabic translation in Vienna?

Each of this colored points that catches the eye may be a trigger to exploration of fascinating stories. Some of these stories, dealing with the translation to English, make the subject of Avraham Roos’ dissertation, and along with other experiments with knowledge visualization of the Haggadah translation phenomenon, can be read on his website.

What does this view reveal? and just as important a question: what does it conceal?

Why is this digital Haggadah special? – The DiJeSt Ground Truth Haggadah

Earlier this week we shared here a digitized Haggadah with Ladino translation and asked for assistance in identifying the edition. On the Hebrew Printing and Paleography facebook group, Noam Sienna, who will soon defend his thesis on “Making Jewish Books in North Africa, 1700-1900” came to our help and found it – an edition printed in Livorno(Leghorn) by Elia Benamozegh in 1867 (Yaari 958, Otzar Hahagadot 1292).

During these days of this highly virtual Passover, the social network is replete with beautiful scanned pages of Haggadot being shared online. A magnificent thread on Haggadot throughout the ages was twitted by Michelle Chesner while cooking for the Seder. There is also a rich variety of the digital texts of the Haggadah shared openly, for example, on the websites of Sefaria and the Open Siddur.

What is unique in our digital Haggadah?

The file we share below was created using the platform Transkribus, which enables its users not only to manually transcribe scanned image, or try to automatically identify the text, but also to train the computer to recognize text of its kind. While OCR – Optical Character Recognition software is extant for many years now, most of it is efficient mainly on standard prints of the most commonly spoken languages. Less so on historical materials, less common scripts, fonts and languages. Recent advances in machine learning enable gaining better results even with special scripts and fonts, and even with handwriting.

Using Transkribus, we analyzed and transcribed the text so that the lines of text are linked to their exact location on the page:

When the data is saved this way, it can be used as “Ground truth” – an example that is used by the computer to train on. The outcome of training is a model that can then be used to automatically recognize similar material. Using the model that was trained on the Tetouan Haggadah, we automatically read a page from the Venice Haggadah printed by Bragadin 1629. The result, though not perfect, is relatively easy to correct. with more data, better models can be trained, and the road opens to automatically read more Haggadot.

A ground truth text, moreover, can be used to train automatic text recognition not only within the Transkribus platform, but in any other tools for text recognition machine learning. The Haggadah Hebrew-Ladino ground truth is available for download here in both ALTO.XML and PAGE.XML format.

A spot-the-difference puzzle for passover, or: help us identify the Jalfon Haggadah!

This is what we managed to find out so far: our ‘Tetouan’ Haggadah, the Jalfon family haggadah was most probably printed in the late 19th century, possibly in Livorno (Leghorn), a Jewish printing hub that produced many Haggadahs with various translations to communities throughout the world. The most similar Haggadahs we found were those produced there, and especially this copy from 1842/3, printed by Solomon Bilforti and Moses Israel Falagi:

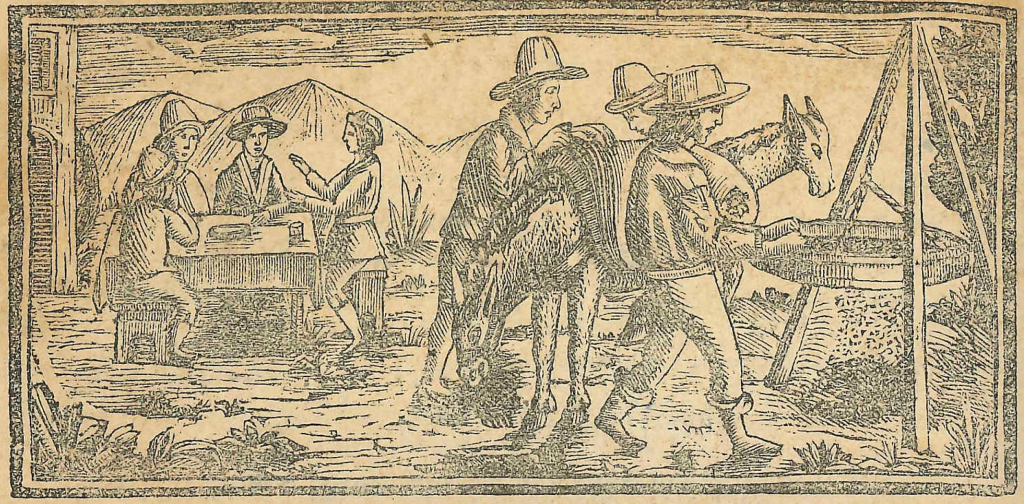

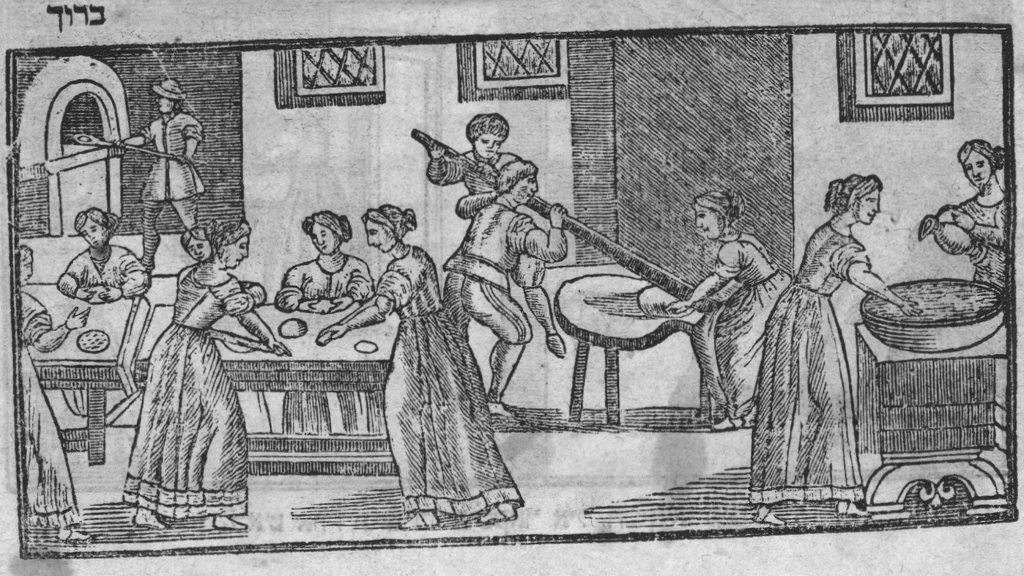

The illustrations of the Jalfon Haggadah, modelled as many other Haggadahs on the 1604 woodcuts of the Venice Haggadah are still rather different than any other Haggadahs we found. Notice, for example, the pictures below: in the first, the Tetouan haggadah, the house on the left has no tiled roof, as is the case in the Bilforti haggadah below it, and and other Livornese Haggadahs we have seen. There are other peculiar differences to be found.

Whether it is as a fun challenge to pass time in quarantine days, for an iconographical study, or for comparison with candidate sibling Haggadahs that might reveal the edition details of the Jalfon family haggadah, all its images are available in this folder .

Meet DiJeSt – DIgitizing JEwish STudies

"Ma Nishtana"(what has changed?), traditionally sung by the youngest child at the beginning of the Passover Seder. In Hebrew from the Sarajevo Haggadah, a famous illuminated manuscript from circa 1350 ce.. Image taken from Wikimedia commons, (last visited April 3, 2020).

Ma Nishtana?

Well, quite a bit has changed and Passover will not be the same this year. It is an eerie occasion, yet especially appropriate, to be unveiling a digital project that aims to make Jewish Heritage digitally open and available for research, accessible beyond limitations of space, and, as it happens, of quarantine.

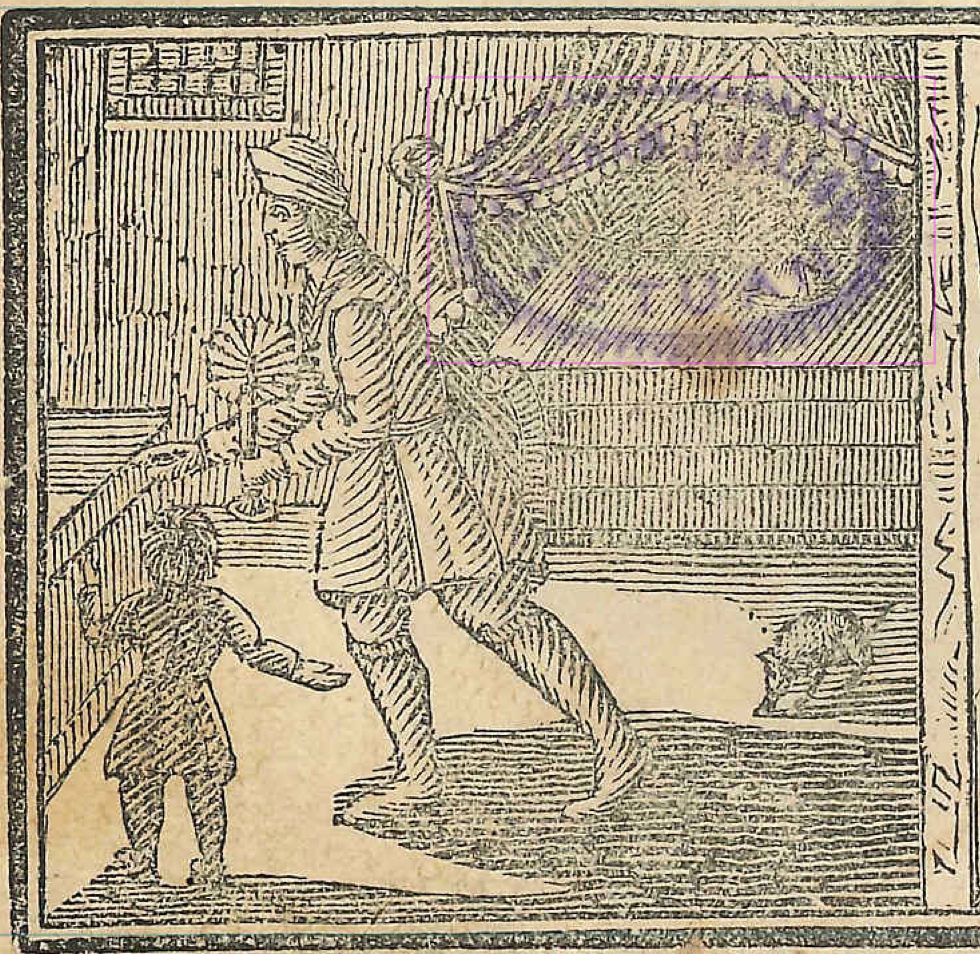

It is even more appropriate to start by sharing as the first digital fruit of our project a family haggadah. This specific 19th century Hebrew-Ladino Haggadah, bearing the stamp of Abraham J. Jalfon (1875-1949) from Tetouan, Morocco, arrived via Spain to Israel with Michel Jalfon, his great grandson, who is one of the contributors to this project.

Abraham J. Jalfon’s stamp

There is much we do not know yet about this copy; It has lost its cover and front page and with it the information about its edition – place and date of publishing, printer and provenance. Some of this we hope to learn from you, the reading and studying community. The answer may lie in reference books on your shelves, or in similar Haggadahs in your families.

During the days of this coming Passover I will post a little about the meaning of its being a digital Haggadah and of the way in which Digital Jewish Studies can approach it, and benefit from it.

For now, you can scroll through the pages of our mysterious “Tetouan” haggadah below. It is a textual PDF which enables search, copy and paste. By clicking the << sign on its upper corner, a menu will open where you can chose to expand the view, print or download. By clicking the opposite corner, you can open or close a panel that will let you browse the pages or alternatively, navigate via a table of content.